Breakfast

Uppermost in my mind was the dying camera battery that I would need to capture the remainder of my journey, whether that be by land or by air. Somehow, it had lasted from home to HALO without a charge, much longer than it had a right to. My battery charger was dual voltage; I just needed something to make the plug fit. Louie produced a universal adapter that I could use. Then he went back to the kitchen to throw together a breakfast for everyone. Louie offered from the kitchen, “does anyone have a preference on the bacon – crispy or soft? No? Crispy it is then.” I went to the kitchen, and Louie offered me something to drink. I chose tea, and Louie put a kettle on the stove. Christy poured himself a mug of coffee. As my tea brewed, Louie filled in some more details for me.

When most of the HALO team went on furlough at the beginning of the pandemic, the three of them stayed behind in Menongue as skeleton crew. The idea was that they would hunker down in Menongue until the crisis blew over. They had just fully stocked the freezer, so they could last quite a while in relative comfort. However, as the days wore on and the pandemic worsened, it was decided that they, too, should evacuate. But they found, as I had, that no domestic flights were available, and overland travel was uncertain at best.

Soon breakfast was served – bacon sandwiches with “brown sauce.” Christy took a sandwich and stepped outside to check on things, and Louie told me a little more about himself. He had been in Angola less than a year. It was too early in his contract to take a furlough like the others, so he was considering staying in Angola to hold down the fort. Because staying in Menongue would put him at higher risk of supply shortages, he preferred to be in a less vulnerable, urban setting like Huambo. As Louie put it, “anywhere but Luanda.”

He gave me a quick rundown of the base. Of course, nothing was going on right then. Normally, the vehicles out front would be in the field supporting demining operations across the province. Cuando Cubango, of which Menongue is the provincial capital, is the most heavily mined province in the country, and normally the base would be very busy. He described the Ops room, where they did their strategic planning, and he said they have a sampling of unexploded ordnance there that they had extracted from the land.

That piqued my interest. “Really? Can I see it?”

“Yeah. Let me just get the key. Follow me.”

After a few steps, I paused.

“Can I take some pictures?”

“Absolutely”

“Let me get my camera”

I hurried to get the battery from the charger and grabbed my camera. Things were getting really interesting. I hadn’t expected to get a tour.

The Ops room was at the end of the long building with the veranda. We entered one of the offices, and Louie asked a man there for the keys. Louie addressed him as what sounded like “Chef Tony” as in “cook,” so that’s what I assumed he was, though it seemed odd that the cook would oversee the Ops room. (And besides, why was Louie making us bacon sandwiches if there was a genuine chef on the payroll?) I thankfully kept those thoughts to myself. I later learned that chefe was Portuguese for “chief” or “boss” and that Chefe Tony was a longtime colleague of Christy’s. They had worked together years ago in a different country on a different project, as well as several years in Angola. It was Chefe Tony who would be in charge of the base in Menongue during the shutdown.

Ops room

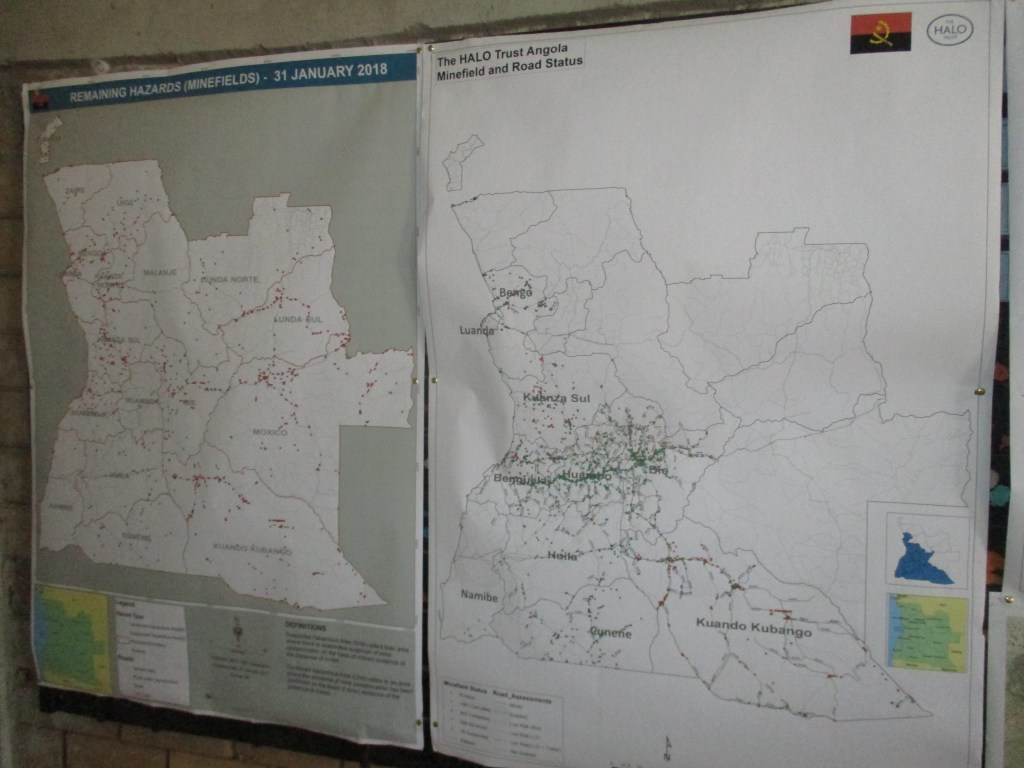

The Ops room was a sparsely furnished space with two tables against the left wall. A large map of southern Angola covered most of the right wall. The rest of the space had other maps of different shapes and sizes, as well as photos and posters showing the nature of HALO Trust’s mission. Color-coded dots littered the maps, designating active, cleared, and suspected mine fields. The dots were clustered in some areas, and in others, they fanned out like a ribbon. The burst of color around Cuito Cuanavale was an unspoken testament to its role in one of the bloodiest and most important conflicts of the civil war.

Collection of unexploded ordnance

Spread out on the tables was a selection of mines and other ordnance . As I snapped pictures, Louie spoke about a few of them. I was surprised to see several rocket-shaped projectiles. One of these was a long, thin missile of solid metal. It had no explosive charge. Louie explained that it was an anti-tank weapon. As the missile penetrated the tank’s armor, the unfortunate crew inside would be subjected to intense pressure, a shower of super-heated metal, and toxic gases, all at once. The high temperatures could also “cook off” the tank’s ammunition, setting off a chain reaction of explosions. And at least theoretically, if the projectile managed to exit the far side of the tank, the resulting vacuum would attempt to pull what was left of the occupants through the hole, adding insult to injury.

I held one of the hand grenades and felt the heft and the knobby surface. It was designed to fragment on detonation, and each individual segment was able to maim or kill. The space for the explosive charge was surprisingly small. I was amazed that such a small charge could fracture such a heavy shell and send chunks of metal in every direction. Of course, it had been deprived of its deadly charge, like all the implements laid before me.

Claymores (like those often found in Call of Duty games), small anti-personnel mines, and big anti-vehicle mines made up the rest of the collection. I expressed surprise at how many of them were made of wood and plastic. He said that many mines were designed with very little metal, perhaps just the firing pin, to give them the smallest signature to thwart metal detectors. Because of this, the use of detectors alone is not sufficient to reliably clear a mine field. He went on to describe the method they employ.

Demining procedure

The area is marked off in a grid pattern. The deminer works on hands and knees, close to the ground. The worker first looks for trip wires or other telltale signs of a mine’s presence. The overbrush is then carefully removed. Using a small shovel and a back-and-forth scraping motion, the deminer slowly digs into the side of the soil looking for the edge of a mine, hoping that the mine hasn’t turned sideways. In this fashion, the deminer removes the top 10 centimeters of soil. Most mines are found near the surface. If there is reason to believe that the mines may be buried deeper (perhaps because of soil erosion or shifting in the area), the depth is extended to 20 centimeters. It is a painstaking process with daily progress measured in mere meters.

Training and armor

One of the pictures on the wall was of an Angolan in the typical blue body armor of a HALO Trust deminer. The design had changed little since Princess Diana donned such protective gear for her tour of Huambo. Louie described to me the balance the armor strikes between protection and mobility. If the workers are burdened down with too much protective equipment, heat, fatigue, and discomfort can impact their effectiveness. As it is, the deminers work 50 minutes and then get a 10-minute break to keep them fresh. A face shield and body armor cover the vital organs and are designed to withstand the most common munitions. One of the HALO ambulances is present at every mine field operation, ready to rush an injured worker to hospital. In the worst-case accident, MAF is on-call for emergency medevac. And of course, each worker receives a lot of training before ever working an active minefield.

Menongue’s “Kuando Kubango” province in the far southeast

Benefits of HALO’s work

The removal of the landmines is essential to Angola’s future economic growth. The mines continue to main and kill; survivors are left without an eye, a leg, a hand, an arm. Farmers often bear the brunt, owing to the economic necessity of cultivating areas that have not yet been cleared of mines. Children are all too often victims, out playing in a field, unaware of the hazards. They might find a munition and play with it, not understanding the danger. Then of course there is the impact on tourism. All else being equal, most vacationers prefer to go where the odds of being blown up is roughly zero.

As we walked back to the bungalow from the Ops room, Louie talked about how minefields are discovered, reported, and marked. They might hear reports from the locals of an explosion, sometimes accompanied by human or livestock casualties. Sometimes the movement of the ground over time uncovers or sets off a mine in a previously unmarked field. They send out a team to investigate. Because of the economic benefits of having a HALO team working in the area, there has been the occasional false report aimed at keeping the HALO team around longer, but they take every report very seriously.

Most commonly, the active minefields are marked with perigo minas (“danger mines”) signs and rough-drawn skull and crossbones. Otherwise, any stick painted red and placed in a visible location can indicate the border of an active minefield. Even with these warning signs, some villagers are forced to live with the danger and try to mitigate the risk by walking only on well-beaten paths through the minefields. He asked me to keep my ears open for any talk that might indicate an unknown minefield; even now, new fields are being discovered and evaluated across the country.